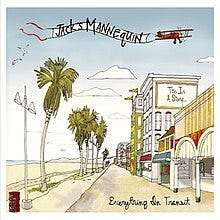

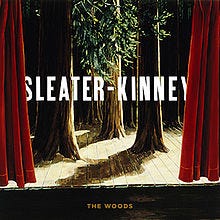

There’s a Sleater-Kinney song called “Modern Girl” that I played on repeat a few years back. I was not cool enough to know about Sleater-Kinney when their album The Woods was released in 2005 (in which “Modern Girl” appears), and definitely not cool enough to worship riot grrl / punk / indie legend Carrie Brownstein just yet.

“Modern Girl” seems more conventional and, for the most part, more upbeat sounding than most Sleater-Kinney songs upon first listen. And if you ignore the lyrics, listening to it as background music as I did at first, you could easily mistake it for a love song. But when you listen to the lyrics closely, it evolves: the song begins with being in love and being happy, as the speaker slowly admits she feels isolated, hungry, empty, and angry at the entire world.

The song reveals layers as it builds and as you listen over and over again if you are, like me, someone who fixates on a song and plays it on repeat. The sweet guitar rifts are eventually joined by sharp harmonica and louder, less pretty vocals by Brownstein.

I’m not going to sit here and say it’s a revolutionary song, lyrically or musically—it’s not. It’s just a song where everything sounds perfect and gorgeous and right, nothing but satisfaction and catchy melody, until you stop long enough to take stock of what Brownstein is singing about.

I revisited “Modern Girl” recently when compiling a playlist for a long drive. And I was shocked how profoundly it hit me upon listening to it as pandemic restrictions lift. I just finished graduate school and am living the precarious life of a freelancer/funemployed person for the first time ever (a privilege, I know).

Folks have asked me how it feels to be done with graduate school, and to my shock, it has felt amazing. But not because of any big exciting plan or news. I, a person who Needs Structure and Needs a Plan (oftentimes to the irritation of those around me), have loved feeling a bit aimless for once, more than I expected to. The job market is terrible, public health still feels precarious, and yet somehow, I feel freer than I have in a long time.

My boyfriend tells me that it all makes sense: I’ve been burned out for a while now and I’ve been vocal about it. So I shouldn’t have been surprised by how much “Modern Girl” bowled me over yet again in the year of our lord, 2021.

How many times have I put on a happy face while teaching or conducting meetings over Zoom these past 15 months? How many times have I tearfully told my boyfriend how burnt out I am by this pandemic, even though I know I’ve had it far better than most? How many times have I lost myself in trash TV, or food, or any number of other vices? How many times have I thought to myself about how lucky I am for the love in my life and my personal circumstances yet felt alone or at a distance from the world, unsatisfied and angry at the systems I am beholden to?

*

Jill Lepore wrote about the history of the term “burnout” recently for The New Yorker, citing its wide array of colloquial uses despite its fuzzy and amorphous clinical history.

What I appreciated about Lepore’s work was the way she could encapsulate just how hard it is to pinpoint what burnout is and how it differs from our permanent state of being, especially given the bizarre pace of pandemic life that we’re slowly evolving out of. Has it always existed? Or is burnout as we know it now something more sinister?

“To question burnout isn’t to deny the scale of suffering, or the many ravages of the pandemic: despair, bitterness, fatigue, boredom, loneliness, alienation, and grief—especially grief. To question burnout is to wonder what meaning so baggy an idea can possibly hold, and whether it can really help anyone shoulder hardship. Burnout is a metaphor disguised as a diagnosis. It suffers from two confusions: the particular with the general, and the clinical with the vernacular. If burnout is universal and eternal, it’s meaningless. If everyone is burned out, and always has been, burnout is just . . . the hell of life. But if burnout is a problem of fairly recent vintage—if it began when it was named, in the early nineteen-seventies—then it raises a historical question.”

I like how Lepore calls burnout “a metaphor disguised as a diagnosis.” Isn’t that how so many mental (and physical) health problems begin? We describe them as images of something else since they are often too difficult to put into words. Sadness, grief, and depression are often described as heavy or living in a hole. Anxiety attacks are often likened to (and mistaken for) heart attacks. Metaphors stand in for names when medicine has not yet caught up to a specific form of suffering.

Lepore asks the right questions here, but I’d also go a step further: what images and metaphors can we ascribe to the particular burnout of post-pandemic life? The strain of emoting with a mask on; the exhaustion of performing on Zoom; the infinite scroll of email and Twitter screens; the perpetual onslaught of bad news; the unfathomable loss of human life.

How do we grieve and make the world “right” again when there’s so much collective trauma to process? How do we allow more space to be happy and joyful while simultaneously angry, tired, and, perhaps, hungry for something better to come out of this catastrophe?

Honestly: just the process of writing this newsletter entry has been hard. I’m still burnt out on writing, reading, and editing. Compared to so many other writers with robust newsletter audiences and Twitter followings, I’ve found myself talking myself out of what I want to say, sure it either will be lost to the void or too full of navel-gaze-y pathos to benefit anyone. I want to write and shout my ideas out, use the years of research on anxiety I’ve compiled, share all of the darlings I’ve killed (but would love to resurrect) now that I have the time to do so.

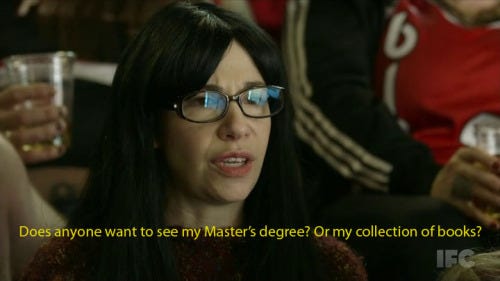

But it’s hard to do. Books have been written on this topic, particularly this one about millennials as the burnout generation. Burnout is a privilege—a sign I have the ability to step back, relax, and process hard work and difficult things—but it’s also a heavy reality. This angst and resentment about my own burnout, and the hunger and anger it causes, are what apparently make me that modern girl Brownstein is singing about.

Maybe this is more a question of perspective and survival. How do we continue to put on a good face and celebrate life when it feels as though we’re all still trying to find our bearings and rest, sometimes barely hanging on?

*

It will not surprise you, dear reader, when I posit that maybe my metaphor for burnout is Carrie Brownstein singing and screaming: “my baby loves me / I’M SO HAPPY / Anger makes me a modern girl,” that strange contradiction of having love and an excess of everything good and being angry at the world nonetheless.

What I want to know are the images and metaphors you’re using to describe your burnout. How do you explain your burnout to the people in your life? What does it feel like, sound like, taste like? I want to collect these images, these feelings, as we emerge from our strange little quarantine cocoons.

Hello, so glad to have found you! I am also writing about recovering from anxiety (and addiction) in narrative/serial form over here: http://surrendernow.substack.com. Thank you for your writing, I will work through the NW back entries and stay tuned for your updates. :-)