There’s scientific evidence that proves that certain sounds, when heard loudly, can make a person physically ill. The sufferer might report nausea, dizziness—they could even faint.

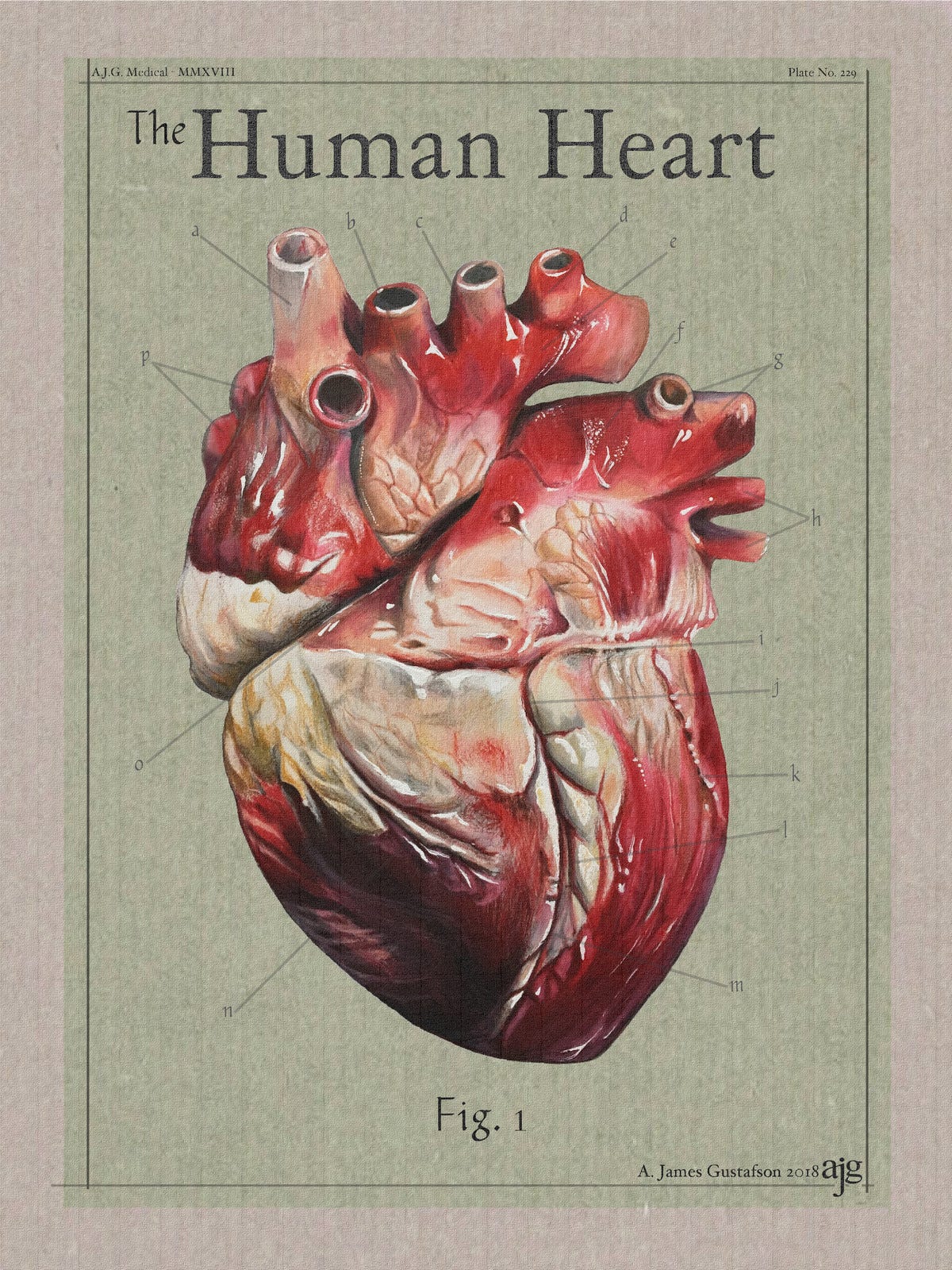

A prime example of this occurred at a live Radiolab event at Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2015. The show featured a story entitled “Tell Tale Hearts,” which required playing the sound of a heartbeat pumping very loudly. The featured story was about a woman whose heartbeat after surgery was so loud it distracted her from her own life. A number of audience members left the theater reported vomiting or feeling nauseous; others reported having panic attacks; and some even fainted.

Radiolab made a follow-up episode discussing this event and explaining the science of why the spectators became ill so quickly. Host and radio journalist Jad Abumrad tells the listener that he had noticed something odd going on during the live event, but that he wasn’t made aware of what was going on until after the show had concluded. In the follow-up episode, he speaks to a psychiatrist who explains that this is a response from the parasympathetic nervous system, which allows human beings to relax (as opposed to our sympathetic nervous system, which is what causes our fight-or-flight instincts towards perceived danger). However, 2-4% of the population’s blood pressure will drop quickly upon, say, seeing blood or hearing a heartbeat, causing them to feel unsettled upon hearing, say, a heartbeat pulsing loudly, echoing through an auditorium.

In addition to relaxing, this can also be an empathetic response, one of connection to another human being’s intimate rhythm. One audience member said that the heartbeat (which played for an extended period of time during the performance), seemed as though it’d go on forever and that she may never escape it. Even thinking back to it, she claimed to feel shortness of breath. She’d felt a strong connection with the subject of the story. She’d escaped the heartbeat and its mystery, yes, but she also enthusiastically claimed that she was eager to hear that story—and the heartbeat—again. She felt drawn to it, and she wanted to revisit it despite her profound physical reaction.

*

For a long time, I thought I wasn’t susceptible to noises that could make me sick. That is, until I recently heard clips of 9-1-1 phone calls and dispatches from 9/11 as the terrorist attacks unfolded in NYC. They were featured in a podcast called “Missing on 9/11,” which documents an investigative reporter’s attempt to solve the case of the missing Dr. Sneha Philip, a Rector Street resident last seen one block from the World Trade Centers on 9/10/01. Part of their reporting, inevitably, dives deeply into the recordings of 9/11 itself. I should have been prepared to hear 9/11 dispatch recordings and phone calls, but somehow, I wasn’t. I became deeply nauseous upon hearing it. It took three separate occasions to sit down and get through the episode in full. This felt important, or perhaps misguided.

It’s not as if I can’t engage with art about American tragedy. In fact, I often find it useful: it is a way to metabolize disaster in a limited and controlled environment. This is not without its problems, of course—cue the “white woman true crime”/“torture porn” discourse—and I don’t begrudge anyone who isn’t into it. I, frankly, don’t know why I’m into it (particularly the more sensational stories) a lot of the time.

Docudrama about American tragedy is popular for a reason—its just distant enough to not feel real, just close enough to fool most viewers or readers. I admire Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (based off the Columbine shooting); Phil Klay’s Redeployment (a short story collection based off of the author’s time serving in Iraq and Afghanistan); Jessica Bruder’s Nomadland (on the collapse of the middle class in America); Sanne Wohlenburg’s Chernobyl, and more.

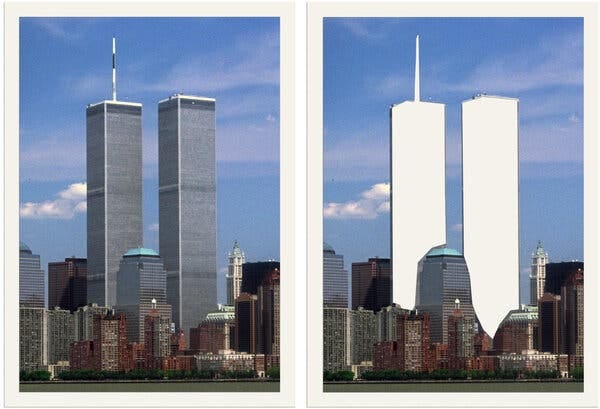

But something about the art trying to accurately depict 9/11 in a variety of ways hits me differently than any other historic tragedy. I cannot bring myself to watch United 93, World Trade Center, or Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. I’ve seen The Woman Who Wasn’t There, about the woman who faked surviving 9/11, but that was a scam story rather than a 9/11 narrative.

There’s the more experimental work (some of which has been catalogued by the 9/11 Memorial & Museum’s Artist Rendering The Unthinkable series) like Spanish artist Monika Bravo’s short film Uno Nunca Muere la Víspera (roughly translated: “One Never Dies on the Eve of Their Death”). Bravo was an artist-in-residence at the Twin Towers, and the film shows footage recorded from the studio she shared with a colleague Michael Richards on the 92nd floor. She had recorded a dramatic thunderstorm the evening before the attacks at Richard’s behest. She was not in the towers when the plane hit, but Richards was—watching it feels like watching an elegy.

I even watched the documentary Into the Clear Blue Sky about Cantor Fitzgerald post-9/11, but found myself deeply distressed the rest of the day, saddened but also weirdly infuriated by the decision to feature some of the more hopeful stories of community at the end, as if that was somehow supposed to resemble a real life happy ending.

And then there are the stories I don’t know, or that I haven’t heard yet, from the Afghan people who have suffered for years after 2001 at the hands of the U.S. military. Some of this is happening now, as podcasts like The Daily and This American Life play audio clips of Afghan civilians fleeing the Taliban in the midst of the U.S.’s ignorantly handled withdrawal. Again, they make me feel sick to my stomach, but still. I feel guilty that despite its immediacy and urgency, a part of me still feels some sense of distance. And yet, I once again could not listen to these audio stories in one sitting either.

But that’s what makes audio storytelling so intensely intimate, more so than mere visuals or written words even—it is as if someone is saying all of this information to you and only you in this very moment. Who will tell the hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugee stories, or at least attempt to depict them? I want to believe that one day those sounds and stories, too, will sicken me in the same way.

*

When I went off to college and made friends who weren’t from the tri-state area, I learned that 9/11 sat differently with them. It was a tragic day, sure, but it wasn’t as close to them. Not in the same way. They did not watch their peers slowly disappear from class into the main office where they received phone calls from their parents or were taken home early.

I have not gone to Ground Zero or the memorial or the 9/11 museum, and I don’t have any plans to. This often shocks friends of mine who aren’t from the northeast, who have already descended into the museum as tourists. I get it and I don’t begrudge them—it is a historical place. But I know that the 9/11 phone call audio plays in the museum itself, and I know I would not be able to bear listening to it in that space. I’d spiral into a panic attack. Unlike the live Radiolab audience members, my sympathetic nervous system would go into overdrive. It would be too much for me to bear.

As lucky as I was on that day, as much distance as I was granted: the day somehow feels close enough to quicken my heartbeat and stunt my breath. Still too close, twenty years later.

*

Despite all of this, I’ve become somewhat-secretly, increasingly fascinated with reading about the aftermath of 9/11. It is only in the past year or so that I even realized just how little I knew about the experience beyond how it impacted me at that time: I’d been a middle-schooler in a suburban Connecticut commuter town when it happened. My hometown was a place from which Metro-North, that vital transportation artery, pumped our parents in and out of the city every day. I knew 9/11 from the periphery at the time, and up until recently, I’d still only known a sliver of its gravity.

I want to engage with art that reckons with 9/11. I want to watch or read or engage with something that can provide…I don’t know. Catharsis? Understanding? A more productive way to hold a heavy memory? I, as a writer, want to write about that kind of feeling some day. But it is so big, and so impossible, and somehow still so fresh.

Will there ever be enough distance? Can any art form really encapsulate that slo-mo walk from the bus to my doorstep on the afternoon of 9/11? Or the relief of hearing my father’s voice on the phone that day? Will any work of art be able to touch the deep heaviness of attending one of the memorial services of the victims, the church so chock full of mourners that folks were standing in the back and out the door? Can any storyteller articulate the seismic effect of 9/11 on the tri-state area, the Boston area, the Pentagon/D.C., and Shanksville, PA—the lives it destroyed and changed?

And will there ever be enough storytellers to document the lives destroyed—and continually being destroyed today—in Afghanistan? And will we ever stop for long enough to care and listen?

*

I was initially hesitant to read the semi-viral essay “One Family’s Struggle to Make Sense of 9/11” by Jennifer Senior at The Atlantic. Once again, I feared that even without the ambient noise of frantic phone calls and dispatches, I’d somehow spiral. But the buzz online was too much to pass up. I clicked the link and read it.

Frankly, it surpassed the internet buzz. Senior does a beautiful job explaining exactly why 9/11 remains such a difficult and mysterious event: for the family and loved ones of those who died, there are no concrete answers as to what exactly happened to them on that day. She recounts the aftermath of the McIlvaine family’s devastating loss of their 26-year-old son Bobby on 9/11. The McIlvaines and Bobby’s girlfriend reckon with the somber mystery of his death in a variety of ways: Bobby’s father becomes a celebrity in the 9/11 conspiracy community; Bobby’s soon-to-be-fiancé clings to his final journal, unwilling to share it for fear of losing him completely; Bobby’s mother represses her memories as much as possible in an effort to forget; Bobby’s brother throws himself into his career and family, aware that his family’s legacy now relies solely on him. Each subject is grieving for the same person, but each handles the mystery of what exactly happened that day in their own unique way.

*

I know why the sound of a heartbeat or a distressed 9-1-1 call activates such a visceral response. It must activate the fight-or-flight response, the opposite of the parasympathy Radiolab attendees experienced. But it’s still a mystery as to why it’s effecting me (and compelling me) so much now. Maybe my body is performing a physical manifestation of delayed empathy, one that’s overwhelming but also useless. These recordings are 20-years-old. I know how this ends. Or rather, how it ends for myself. In other words: there is no rational reason for me to fear these sounds or to brace myself. The impact has already happened. In fact, the impact is still rippling in Afghanistan.

As an adult, it’s like I’m bracing myself for the anniversary of the attack because now, I know just how terrifying it must have been for the adults around me. Most of the news, when I was 11, meant so little, or maybe I was sheltered from it. And it is only now, with two decades more understanding, that my body can truly feel—and reckon with—the weight of that day, the onslaught of nerves firing all around the world. Now, I’m deeply disturbed by the idea that we don’t know, and we can’t know, so much of what happened that day. What we cannot fully imagine will always haunt us the most.

So the twentieth anniversary of 9/11 is upon us, and I’m suddenly trying to watch documentaries about that day, revisiting the few stories I had known while learning more; listening to podcasts where reporters play snippets of 9/11 phone calls, knowing full and well that it’ll hurt to hear. This strange landslide of new media about the attacks even made the New York Times—one of their critics asks what a 9/11 documentary is even supposed to do decades after that “fateful” day (hell, I haven’t even touched upon 9/11’s impact on fiction yet).

These works certainly aren’t relaxing in the way most entertainment is designed to be (sympathetic? maybe. parasympathetic? not really). And any documentary worth its salt shouldn’t just be dwelling in the sadness and chaos of the day, but oftentimes that’s all they can do—how much can we say about what we cannot know?

And hey, I know full and well the reasons for this glut of media right now: it’s all corporate decisions made to capitalize off of a national tragedy (guilty as charged). These corporations know full and well that a great many of us who were once children unable to grasp the events in real time are now also scrolling through this anniversary driven, grief-laden day as adults.

I’d like to imagine I’m not alone in this particularly grim form of doom-scrolling. Perhaps I’m having one big, long “sympathetic” response to a tragedy that has long since past. It is that retroactive guilt I feel: the anguish, anxiety, disgust, despair, the newly heightened terror, but most of all, the willingness to keep listening anyway.