This newsletter features some discussion of a minor outpatient OBGYN procedure. I don’t describe it in graphic detail, but if it’s not something you’re up for reading, feel free to skip this one.

Recently, I watched Deadwood for the first time. Yes, it is 20-year-old prestige television. It is also one of my husband’s favorite tv shows of all time. I resisted watching for a long time because I find Westerns boring regardless of the medium. But Deadwood is, as my husband insisted, something else entirely.

Anyway. One character, Calamity Jane (based loosely on a real outlaw of the same name), spends all three seasons of the show plus a bonus movie mourning her friend Wild Bill Hickok (also based on a real outlaw). She drinks herself into stupors over it. She tells story after story about him despite him only being in like the first two episodes before he’s murdered. It becomes almost laughable—like babe, he was an outlaw, what did you expect? Get your shit together! Move on with your life!

I didn’t really understand the whole appeal of the outlaw as a trope. Until this week, that is.

The outlaw always gets caught, right? Goes out in a blaze of glory? So why are we rooting for the outlaw? Why do we think the outcome will be different this time?

I am going to tell an insurance story. But it is not a traumatic one, not one that ends in rage and heartbreak like so many I’ve seen posted this past week. It is, if anything, profoundly mundane.

Almost two years ago, I had my annual OBGYN exam thanks to my husband’s medical insurance coverage (I was adjuncting at the time, meaning I did not qualify for it by myself). I love this particular doctor for many reasons, some of which I mention here, but one I need you to know for colorful reasons is that her office building has a strip club at street level. So of course I love her.

Anyway. At this exam, the OBGYN found a small growth on my cervix. Apparently this little thing was responsible for some of the occasional spotting I’d experience between periods. She explained that it was likely a polyp and that so long as my pap smear came back clear (which it eventually did), it would only require a quick outpatient removal.

My doctor was giddy as she told me this—apparently she loved to remove cervical polyps. She found it satisfying, like watching pimpling popping videos after an edible kicks in. But she did tell me that while it wasn’t an emergency, I still needed to have it removed soon. If it got much larger it would require surgery and general anesthesia.

While it was kinda cute in retrospect to see how happy this all made her, I was far from giddy in the moment. Not at all. A growth? Down there? I tried asking her questions about how this could happen, what could have caused it, was it my fault it was there to begin with? She merely waved her hand, saying it was likely nothing.

But I simply couldn’t trust that it was nothing. I’ve read the health insurance horror stories. I lost sleep. I had nightmares: that it was cancer, I needed surgery, I was incurably diseased.

Isn’t this how all medical horror stories start? The doctor isn’t worried until they suddenly are? My brain insisted upon playing out every possible bad scenario, powered by my constant worry-fueled WebMD searches, all of which said I was most certainly on the brink of death. What if this was bad and sent my husband and I into serious debt? What if I became a drain on the people I love?

All of this from a little growth I never even knew was there.

It was another six weeks before I could have the procedure. It was uncomfortable but quick, awkward but ok. My doctor offered to show me the polyp after she removed it. And of course I said yes. I wanted to see the little fucker that had disturbed my sleep for the past month and a half. It was a little fleshy pinto bean floating in fluid. Small but significant, in my brain at least. As with all monsters, the moment I saw it, my fear ebbed away. My imagined polyp was so much scarier, bigger, vulgar than the actual thing, which I could now see in all its boring detail.

“I just love taking these out, y’know?” My OBGYN said with a smile on her face. I love that she loves her job and all but no, actually, I don’t know. This was a relatively common procedure for her. But I only take a scalpel to words at my day job. Not other people’s cervixes.

On my way home I bought myself a lemon seltzer at a bodega. The moderate pain began to hit as the Q train shot out into the daylight on the Brooklyn Bridge. I squeezed the closed plastic bottle like a stress ball. The rest of the day I felt that pain, like bad period cramps. I was lucky to schedule this procedure right after my semester ended so I had a day or two to take it easy with a heating pad and a season of 90 Day Fiance.

Eventually a lab would conclude that this was, in fact, a benign growth. The doctor was right. Insurance even offset a bit of the cost.

Why even share this story? Who cares?

This was the best case scenario in every sense of the word: I had good insurance that mostly covered a good chunk of the cost; a kind doctor who was proactive and positive; an outcome that was straightforward and easy. And even still, I lost sleep. I feared a diagnosis of something more serious. I worried that I had something within me that might mean a lack of coverage, the possibility of serious medical bills, an end to my life as I know it.

I am lucky in that I haven’t (so far) had massive medical bills that put me into serious debt. But I know several folks my age who have. I have soothed more than one person waiting for test results or facing a medical crisis that could ruin them not only physically and emotionally, but financially as well. Almost every married couple my age that I know (including me and my husband) obtained a domestic partnership at the city clerk’s office before getting married, solely for health insurance that may or may not help offset potential disaster.

In other words: here in America, health (and medical insurance) anxiety is the heavy thundercloud that always looms. It changes the way I approach my, and everyone else’s, future. We’re all one calamity away from disaster and ruin at the whims of an insurance company: cold, impersonal, and powerful.

There’s been a lot of not only hand-wringing this week about the death of the CEO, but also many heavy-handed explanations about why the internet has been bursting with memes celebrating the shooter. I’m not here to offer one of those.

Instead, I am here to offer my sympathy for Calamity Jane and her desire to cling to the memory of her dear outlaw friend.

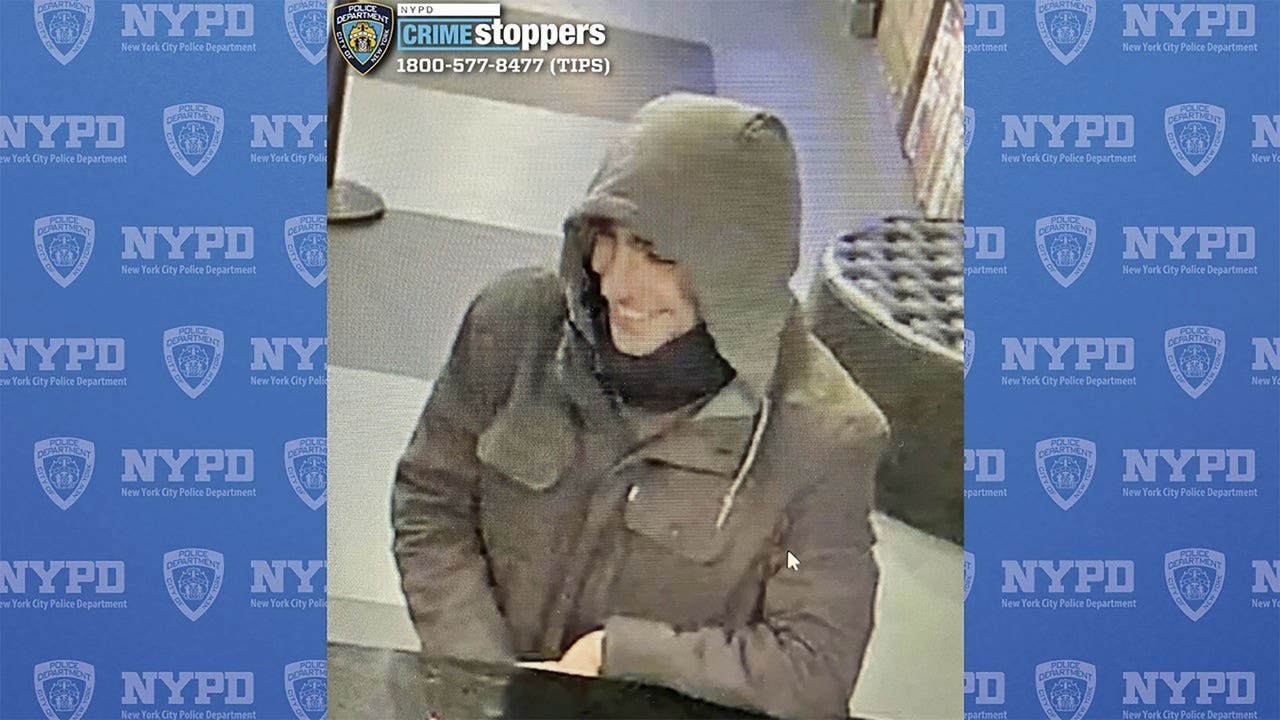

Because this past week, my friends and I rooted for the outlaw. He’s not dead now, just arrested, but what I realized is that the mystique of the outlaw is sometimes held at a remove from the vigilante justice and violence they commit.

The outlaw has to be held at a distance from everyone else to be considered an outlaw at all. Mythmaking happens at a remove.

We see this play out throughout history. DB Cooper jumped out a plane with a helluva lot of cash and was never seen or heard from again. Was he a spy? A folk hero? The world’s most mysterious robber? Without answers, we’re left to fill in the blanks, a Mad Lib that is far more fun and funny than our own lived realities.

Calamity Jane holds Wild Bill Hickok in such high esteem that she’s willing to drink herself to death to be near him again, despite that being the opposite of a glorious death for a wiley outlaw. Her grief eclipses the values she and Bill once held because he has entered the realm of myth for eternity.

Despite claiming he was her best friend, I as a viewer get the sense that Calamity Jane only knew some parts of Wild Bill. He protected her. He loomed large as a symbol of hope for Jane. Part of what she mourns isn’t his presence in her life, but the hope she pinned on him to serve justice and do good in a lawless territory filled with misfits, many of whom wouldn’t think twice about hurting her and her loved ones.

And dead outlaws cannot disappoint us. For all Jane knew, one day Wild Bill Hickok might’ve disappointed her, or betrayed her. But so long as he is dead, he can be saint-worthy.

Sure, I’ve been loving the memes and the jokes about the gunman online. But part of why is because it is easy to imagine myself slipping under the gunman’s spell when I know little to nothing about him. I can remember the fear and dread and anxiety awaiting on my own health news, the dread when the final medical bill arrived even after a best case scenario. So long as I know nothing about him, it was easy to project sainthood upon him, just as Jane did Bill.

Part of why Calamity Jane herself isn’t really viewed as an outlaw within the show, despite her years of working alongside Bill and the many ways in which she is “othered,” is because we see so much of her flawed humanity. She puts a penny in a jar every time she swears (which she does constantly). She likes telling the children in the camp her adventure stories. She falls in love with a madam named Joanie. Wild Bill, the long dead mystery man, gets to stay a mystery. Calamity Jane is all too human because her heart is beating and alive right in front of us, and as a viewer I love her for that. Even if it means she loses some of her mythic outlaw status.

It was for this reason that, despite my sympathy for the CEO’s loved ones, I still rooted for the anonymous gunman. After all, I can hold multiple conflicting emotions at once. I cheered when they found the backpack full of monopoly money and swooned over his cheesy grin at Starbucks. He was, in the words of the always sage Sarah McLachlan, building a mystery. We only knew scant details, and so he was a hero, something super-human I could project my anxieties and values upon like a scrim.

An outlaw looms large because of the principles they hold. The boldness he exhibits. The willingness to die for what he believes in. He’s not violent indiscriminately—he is violent for a specific cause, for the greater good (at least in theory).

So if we see the outlaw too close up and we see their intimate workings—his Goodreads account, his favorite Pokemon, his thirst traps—he becomes too human, too flawed. Put another way: I cannot see this guy as mythic when he is just like every other dude under 40 on the internet.

I am not one of the Americans the gunman spoke for explicitly. Not yet anyway. I will live to see many more days (though the pinto bean did not).

But I would be lying if I said I didn’t root for the outlaw when he was only a smiling face in a Starbucks. And that a small part of me still does, against my best judgement. Like Calamity Jane, it is easier to label someone a saint or martyr when you don’t know their preferred McDonald’s order or their opinion of Jordan Peterson.

I wanted to see him ride horseback into the sunset so, like Calamity Jane telling stories to the children of Deadwood, I could tell a tale of hope about him over the fire, rather than a terrifying tale of a time my body nearly betrayed me. (And yes, we know he suffered from chronic back pain, so he likely wouldn’t ride a horse, but follow me for just a second).

Despite my love of horror movies, this wasn’t the narrative I craved. 2024’s given me plenty of other scary stories.

Grief and mystery and anxiety make for a volatile friend group. Together, the three of them bring out the worst in each other. But all three can agree on one thing: they love a renegade, an outlaw, a story without closure, a growth tucked away, a mythical person without flaws or problematic takes, a silhouette forever too far off towards the horizon to see with any clarity.